Orchid's team of genetic experts has developed a genetic risk score (GRS) for rheumatoid arthritis.

Written by Orchid Team

Orchid has developed advanced genetic risk scores (GRS) for a variety of diseases. Here we present our data on our GRS of rheumatoid arthritis.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by persistent inflammation of the joints, driven by an immune response to the body’s own proteins. It commonly causes joint pain, swelling, stiffness, and progressive joint damage. It can lead to irreversible disability and complications affecting the lungs, heart, and blood vessels if inadequately treated. Women are more likely to develop RA than men, and exposure to smoking can increase risk.[1]

Genetic Risk Score

RA is shaped by both environmental and genetic factors. Monogenic testing is not available because no single gene causes the condition. Genetic risk scores (GRS), which combine the small effects of many variants into a single score, are currently the only way to estimate genetic risk. Although not diagnostic, a GRS can indicate how likely an individual is to develop the disease.

Orchid’s RA GRS was trained following current industry standards.[2][3] The GRS was constructed using the SBayesRC algorithm trained on publicly available FinnGen and Million Veterans Program summary statistics.[4][5] The summary statistics include 30,321 cases and 925,695 controls.[6] The resulting GRS contains over a million variants.

Risk predictions are adjusted to each individual’s ancestry, with predictive power decaying as genetic distance from the predominately European training data increases.[7] Orchid considers a GRS meaningfully predictive if individuals at roughly the 97.7th percentile have an odds ratio (OR) of 2. The RA GRS meets this criteria for all common ancestry groups.

Clinical Impact and Prevalence

RA affects approximately 2.7% of adults in the US.[8] Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis focuses on starting effective therapy early and adjusting it over time to reduce inflammation, prevent joint damage, and maintain physical function. Current strategies aim for remission or, if that is not achievable, low disease activity through regular monitoring and timely changes in treatment. Although RA cannot yet be cured, modern treatment approaches have substantially improved symptoms, long-term outcomes, and quality of life for most patients.[1]

Performant Risk Stratification

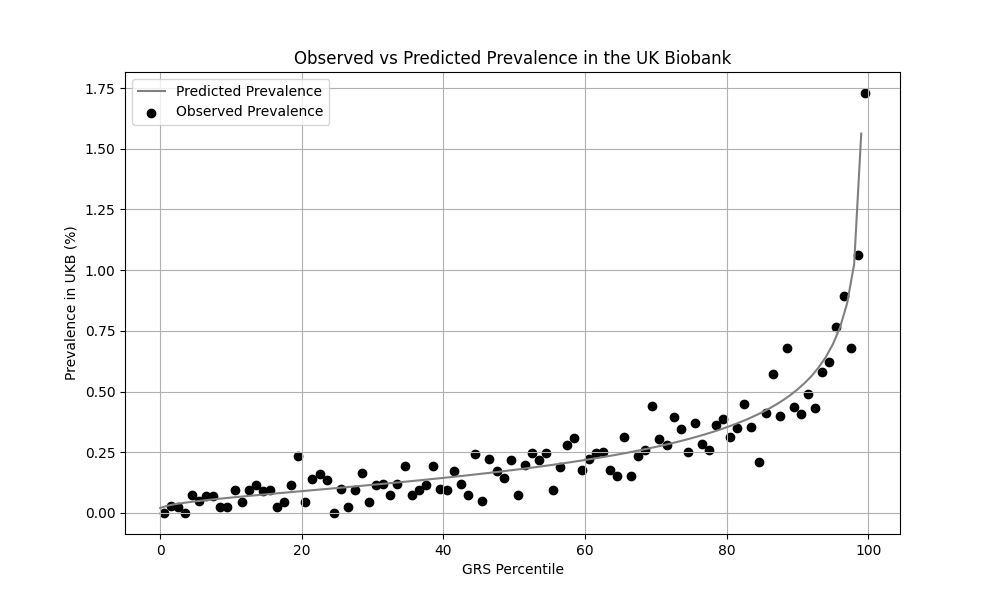

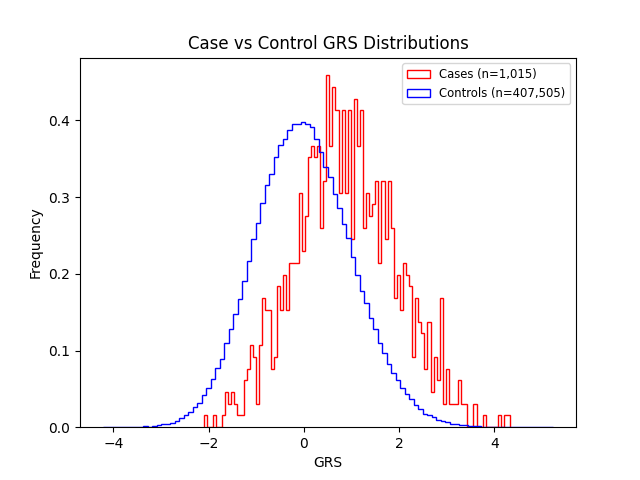

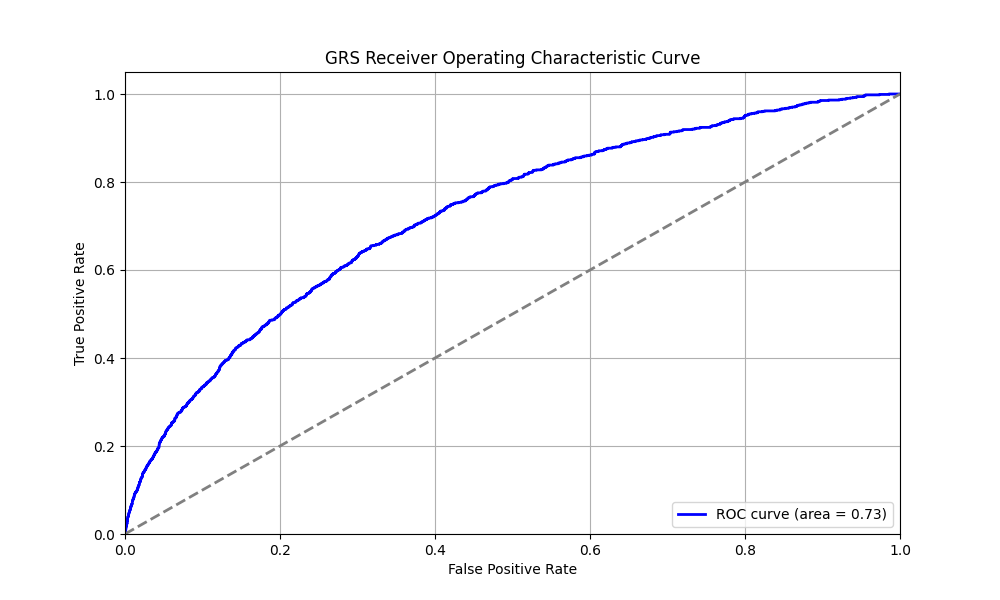

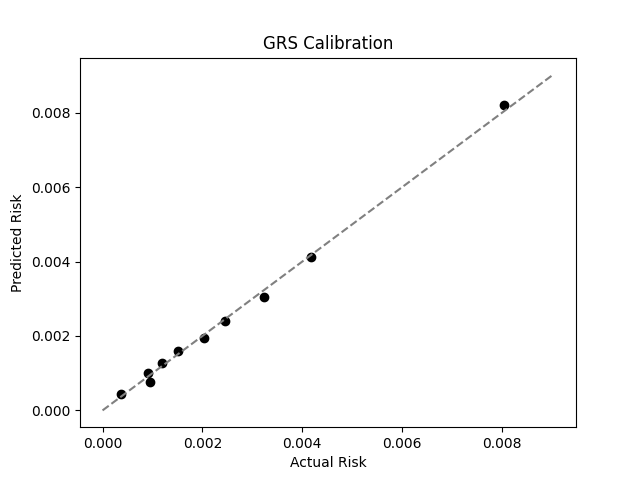

We evaluated the predictive performance of Orchid’s RA GRS using the UK Biobank (UKB), a research database of roughly 500,000 genotyped individuals from the United Kingdom. We restricted the analysis to participants of British ancestry and defined RA using the M05.x ICD-10 code, yielding 1,015 cases and 407,505 controls (0.2% prevalence). We then grouped individuals by GRS percentile and compared the observed disease prevalence within each group to our model’s predictions (Figure 1). For additional technical details, see the Supplementary Data.

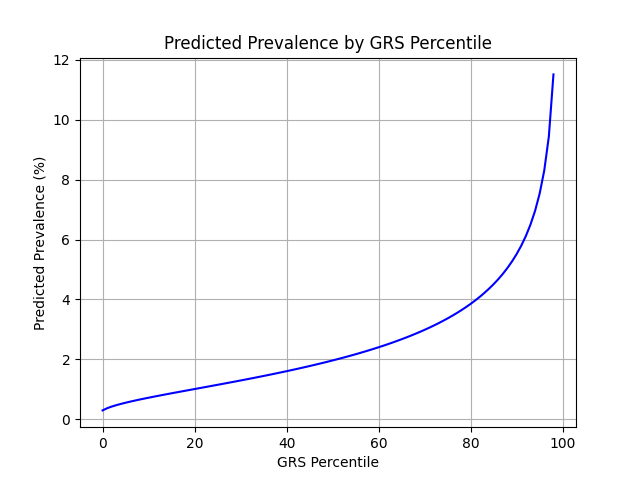

UKB participants tend to be healthier than the general population, which leads to lower observed disease prevalence.[9] Crowson et al estimate a 2.7% lifetime risk of RA, much higher than the prevalence in the UKB.[8] We adjust our model so that its average predicted risk aligns with this estimate (see Figure 2).[10] People at the tail end of the GRS distribution were at an elevated risk compared to the mean (see Table 3), with adults in the 99th percentile 4.4x more likely to develop RA than average (11.5% vs 2.6%).

References

1. Smolen J, Aletaha D, Barton A, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18001. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2018.1

2. Moore S, Davidson I, Anomaly J, et al. Development and validation of polygenic scores for within-family prediction of disease risks. medRxiv. 2025. doi:10.1101/2025.08.06.25333145.

3. Cordogan S, Starr DB, Treff NR, et al. Within- and between-family validation of nine polygenic risk scores developed in 1.5 million individuals: implications for IVF, embryo selection, and reduction in lifetime disease risk. medRxiv. 2025. doi:10.1101/2025.10.24.25338613.

4. Zheng, Z., Liu, S., Sidorenko, J. et al. Leveraging functional genomic annotations and genome coverage to improve polygenic prediction of complex traits within and between ancestries. Nat Genet 56, 767–777 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-024-01704-y

5. FinnGen. FinnGen+MVP+UKBB Summary Statistics. Available at: https://mvp-ukbb.finngen.fi/about. Accessed 2025-12-05.

6. FinnGen. FinnGen+MVP+UKBB Phenotypes. Available at: https://mvp-ukbb.finngen.fi. Accessed 2025-12-15.

7. Privé, Florian et al. “Portability of 245 polygenic scores when derived from the UK Biobank and applied to 9 ancestry groups from the same cohort.” American journal of human genetics vol. 109,1 (2022): 12-23. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.11.008

8. Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Myasoedova E, et al. The lifetime risk of adult-onset rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(3):633–639. doi:10.1002/art.30155.

9. Fry A, Littlejohns TJ, Sudlow C, et al. Comparison of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of UK Biobank participants with those of the general population. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:1026–1034. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx246.

10. Chatterjee N, Shi J, García-Closas M et al. Developing and evaluating polygenic risk prediction models for stratified disease prevention. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:392–406. doi:10.1038/nrg.2016.27

Supplementary Figures

Acknowledgements

This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 80545.